The Heart of Bicol

For the children of first-generation immigrants to a different country, the rediscovery of one’s own indigenous culture does not come without complications. Join Nina Raneses as she recounts how she and a cohort of her fellow students “rediscovered” and reclaimed a pre-colonial script from Luzon called Baybayin. Displaced by the Latin alphabet through Spanish colonisation of the Phillippines, the script is instrumental in helping younger Filipino students rediscover the culture that was left behind generations ago.

NINA RANESES // FLAT HAT MAGAZINE

Last semester, I helped resurrect a dead script.

It might not be the one you usually hear about — there’s a good chance you’ve never heard of it before. In fact, it is the writing system of my ancestors and I had never heard of it before I took Filipino Diaspora Studies, an Asian and Pacific Islander American studies course, last semester. As a visual learner, I was fortunate that my professor, Roberto Jamora, is an artist by trade. Through his expertise and talents, I was able to learn the history of my family’s country through the intricate patterns of textiles, traditional dance and music, and the curves and bends of a pre-colonial ancient script, called Baybayin.

Baybayin was an ancient writing system used for centuries that was eventually replaced by the Latin alphabet as a result of the spread of the Spanish language during colonisation. Though far from the only writing system used in the pre-colonial era, as the Philippines is home to a multitude of languages and dialects across its many islands, Baybayin was mainly used in Luzon, the island of my ancestors.

Younger Filipinos are reclaiming and reviving the use of Baybayin, as the desire — or rather the need — to reconnect to indigenous and pre-colonial roots has become more important than ever to many, both at home and among the diaspora.

“Younger Filipinos are reclaiming and reviving the use of Baybayin, as the desire — or rather the need — to reconnect to indigenous and pre-colonial roots has become more important ever to many, both at home and among the diaspora.“

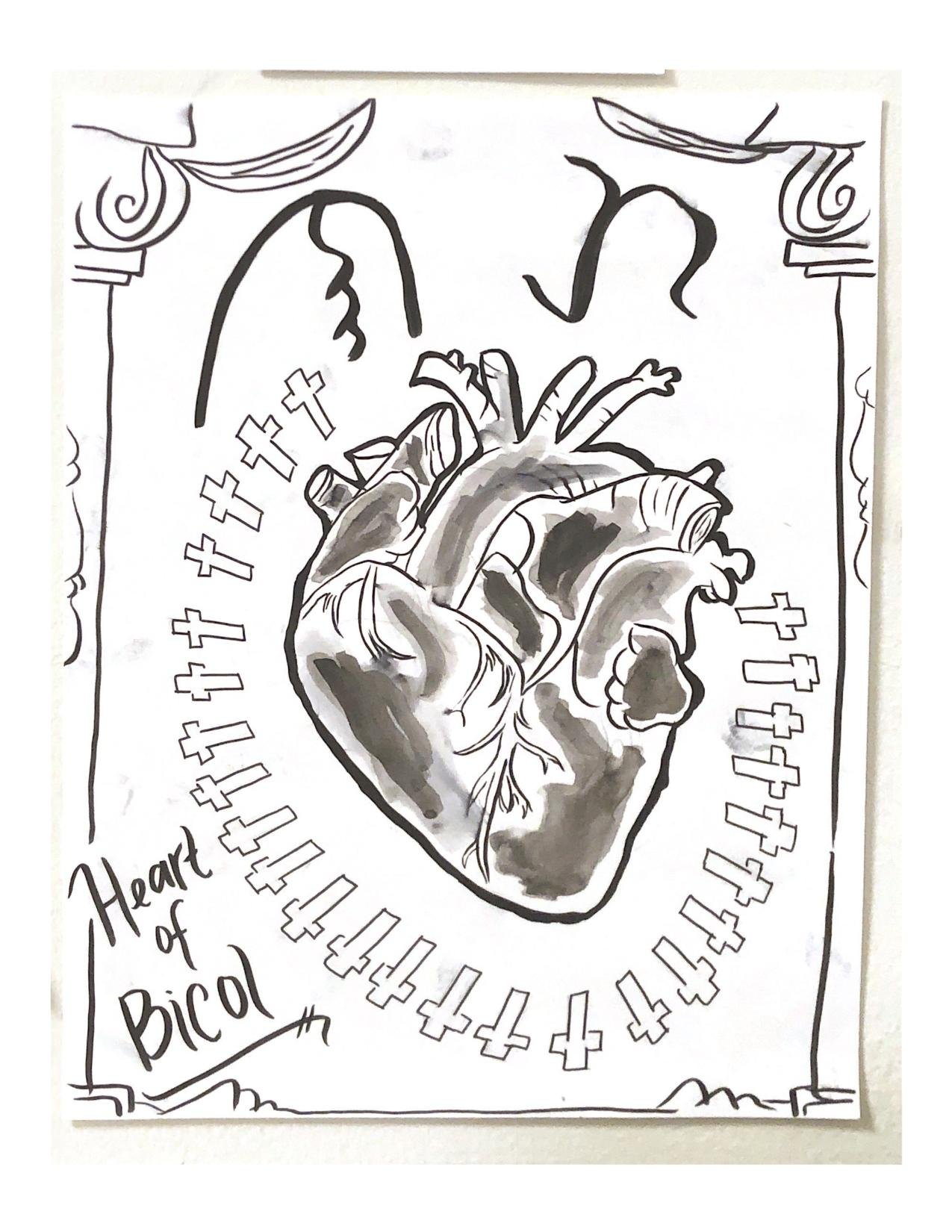

Despite class being held over Zoom, there was still something so remarkable about sitting down in front of my laptop, brush in hand, getting ready to paint these characters alongside my professor and my peers, especially after reading and learning about the script’s history. It meant so much to be a part of this revival. Along with my peers, I painted characters and phrases I’d never heard of until weeks prior — a system embedded in my own heritage for generations upon generations, kept under wraps until now.

Language had not always been a complicated topic for me to think about or discuss. Coming from an immigrant household, people ask if English is my first language, or if there are other languages spoken in the home. Filipinos always ask me if I know Tagalog, which is one of the most wildly spoken Philippine languages. I always pause and think about my response. No, I don’t — and there’s inherently some shame or embarrassment on my end telling other Filipinos that I can’t speak my family’s mother tongue, especially when they ask the follow-up: do your parents speak the language?

“There’s inherently some shame or embarassment on my end telling other Filipinos that I can’t speak my family’s mother tongue, especially when they ask the follow-up: do your parents speak the language?“

The American culture of assimilation made this an easy decision for my family and many like mine. It’s a double-edged sword: raising a first or second-generation immigrant to embrace one language would ideally advance the culture of assimilation for future generations. For the longest time, I didn’t understand and therefore didn’t care about the implications of not knowing the language of my heritage. Living in the United States, not knowing Tagalog has only affected my life every so often, in conversation here and there, and there is an inherent privilege in this fact.

Regardless, in one way or another, language connects me with my family. The silver lining of my not being fluent in my mother tongue means that the language takes on a whole new meaning. It is a meaningful, under-the- surface way of connecting with my family and the diaspora. I take pride in the little I do understand, and living in the Philippines in the past few years has helped me understand even better. Though I am too shy to initiate conversation, I can hear the progression in my understanding when I hear my family speak or when I’m back in the Philippines, and I pick up every few words. For me, the baby steps have been worth it. I have stopped beating myself up for what I do and do not know, as it wasn’t my fault to begin with.

Despite being past the prime age to pick up a language, I celebrate what I’ve put together despite being late in learning more about my own culture. In this way, it has been more meaningful for Tagalog to be this halfway bridge to my own culture. I think my relationship with the language represents my cultural identity well — though my American side is most prominent, there is a special place in my heart for my Filipino heritage, and every day it grows. I proudly display my Baybayin artwork in my room; it’s my little piece of home I created myself. It is the perfect mix of my two cultures — and it shows my dedication to learn and re-learn my perception of the history of the Philippines going forward. I have always been drawn to art and learning by visualising — and the beauty of language is its ability to awaken two of our senses.

I have the APIA programme and courses like Filipino Diaspora Studies to thank for helping me connect parts of my heritage to my education in ways I hadn’t seen possible. I can only imagine the impact this sort of education can have for people with even smaller connections to their roots than someone like me, and how life-changing that education can be. I look forward to spending the rest of my life on this journey and one day passing down what I know to future generations. I’ll never forget making that first brushstroke on a fresh sketchpad in the corner of my dorm room. I’ll always treasure the beauty in the journey a script took from being such a distant part of my lineage to appearing before my very eyes after all that its country of origin had endured — occupations, wars, violence, revolution, independence, transition, and reclamation.

“I’ll never forget making that first brushstroke on a fresh sketchpad in the corner of my dorm room. I’ll always treasure the beauty in the journey a script took from being such a distant part of my lineage to appearing before my very eyes after all that its country of origin endured...“

We have the dedication and passion of our educators, like Prof. Jamora and many more in the College’s APIA programme, to bring an ancient script across both an ocean of time and the literal thousands of miles that separate our home from our ancestral one. Through this education, no one will ever be able to take away our heritage from us ever again.

NINA RANESES // FLAT HAT MAGAZINE